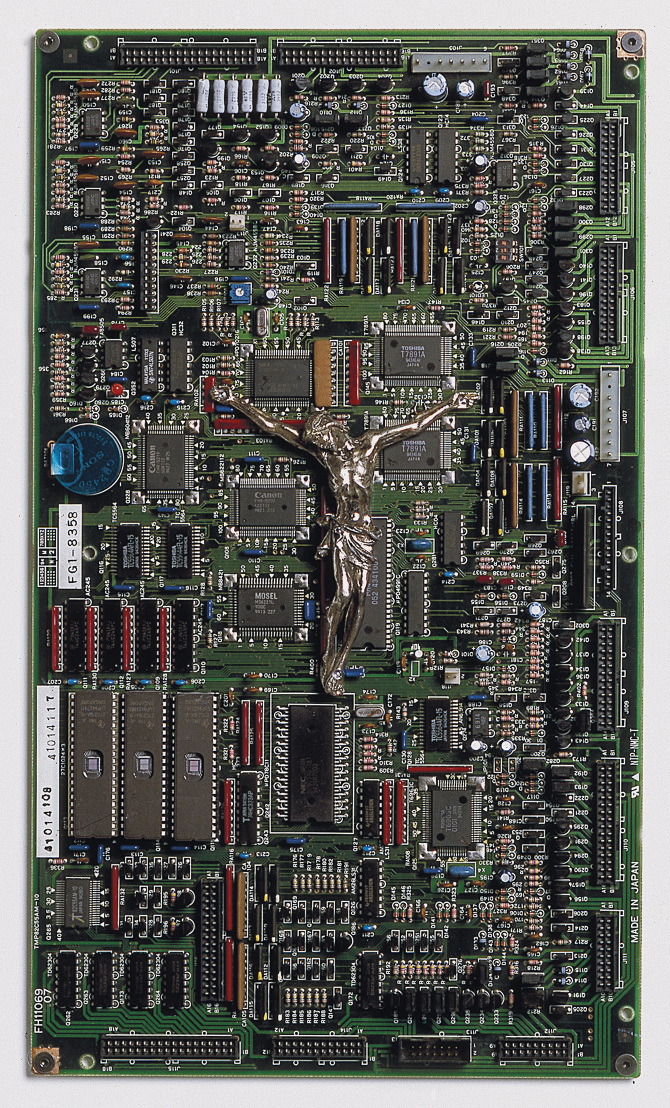

RUGZOX, Dead Internet (2025), Digital collage

RUGZOX, Dead Internet (2025), Digital collage

Historical and Symbolic Meaning of Jesus’s Crucifixion in Christian Iconography

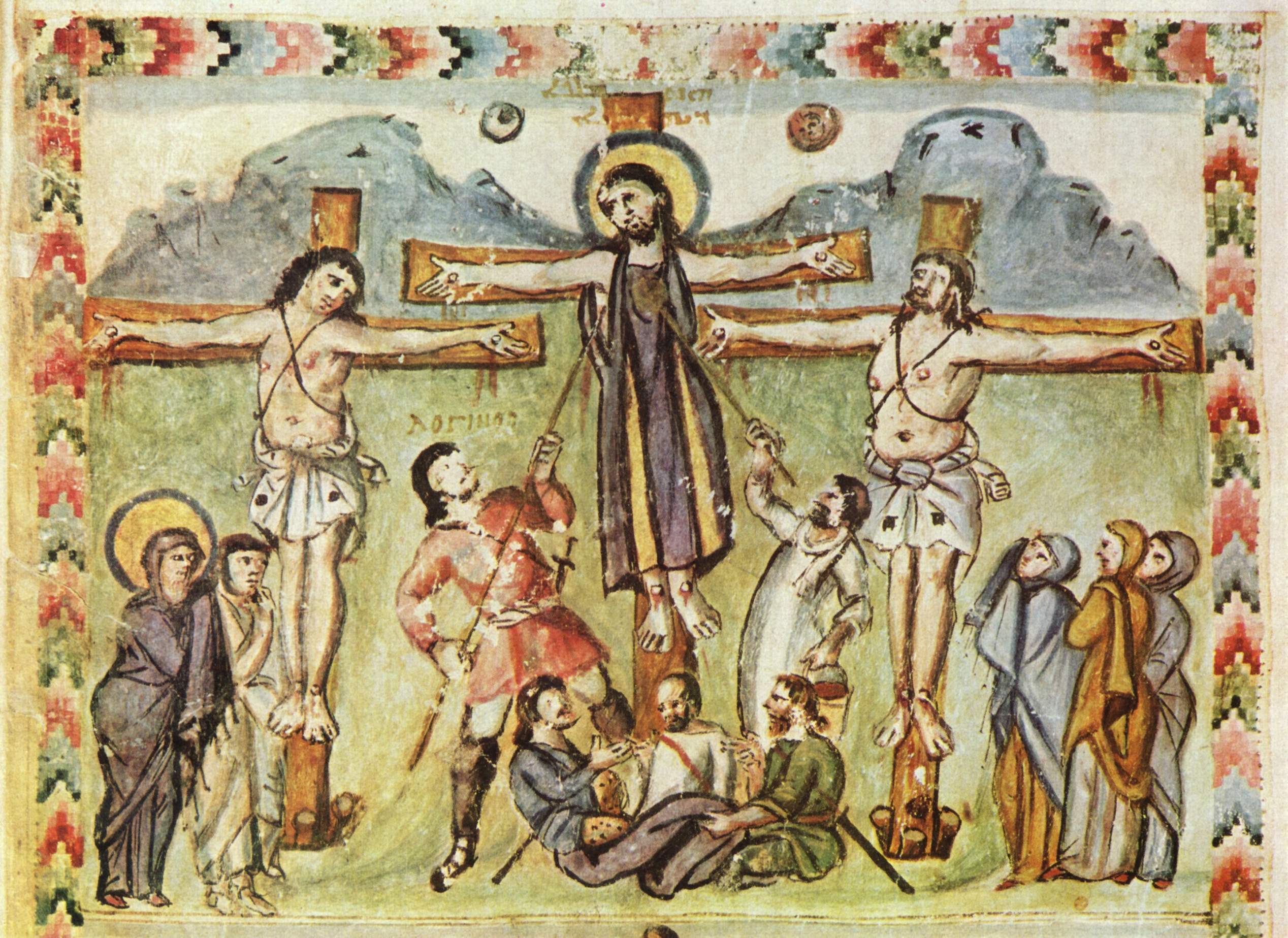

The crucifixion of Jesus is one of the most pivotal events in Christian tradition, laden with history and symbolism, and it has been depicted in countless works of art. From the early centuries of Christianity, artists portrayed Christ on the cross – as early as the 4th century, images of the Crucifixion appear in art, often showing Jesus on the cross with mournful onlookers like the Virgin Mary and angels. In Christian belief, this scene carries a profound meaning beyond a historical execution: Jesus, though innocent, sacrifices himself for the sins of humanity. Thus, the crucifixion stands as the cornerstone of Christian faith, symbolizing the ultimate act of love, sacrifice, and redemption. According to Christian theology, Jesus’s death on the cross (followed by his resurrection) restored the relationship between humankind and God, offering believers forgiveness, grace, and the hope of eternal life.

The earliest crucifixion in an illuminated manuscript, from the Syriac Rabbula Gospels, 586 CE

The earliest crucifixion in an illuminated manuscript, from the Syriac Rabbula Gospels, 586 CE

Over time, the cross – once a tool of brutal Roman execution – transformed into the most recognized symbol of Christianity. A device of pain and shame became, paradoxically, a sign of hope and salvation. In Christian art and worship, the image of Christ on the cross embodies both the tragedy of suffering and the promise of victory over death. The crucifix, bearing the figure of Christ’s broken body, reminds the faithful of the price of redemption, while the empty cross (without Christ’s figure) stands for the Resurrection and the triumph of life. Across centuries, this potent symbol has not remained confined to pious devotion; modern artists have often employed crucifixion imagery to make statements outside traditional Christian iconography, sometimes even for shock value. This enduring power of the crucifixion motif – as an image of sacrifice, suffering, and ultimately hope – forms the backdrop against which the artwork in question boldly reinterprets the scene in a new, technological context.

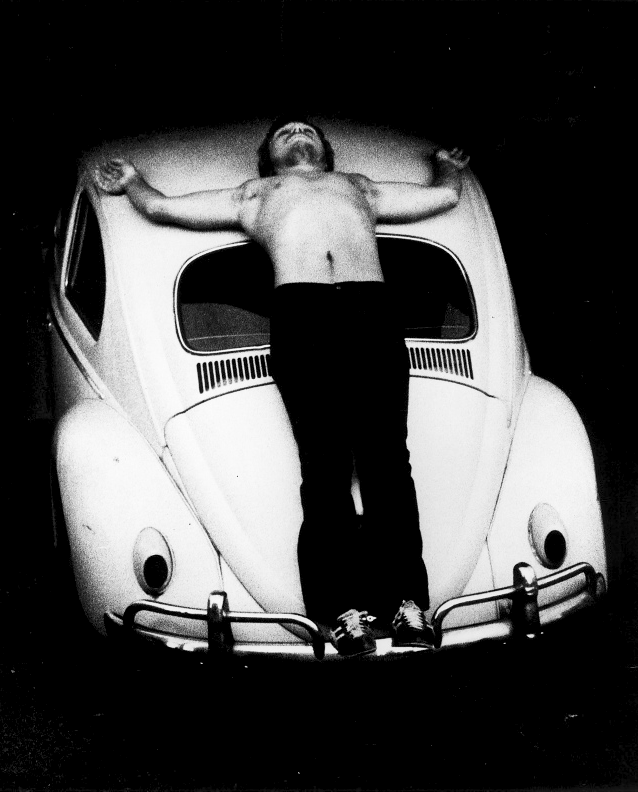

Chris Burden's 1974 performance piece Trans-Fixed, in which he is crucified on a Volkswagen

Chris Burden's 1974 performance piece Trans-Fixed, in which he is crucified on a Volkswagen

The Evolution of Technology and the ‘Death’ of the Internet: A Summary of Dead Internet Theory

Fast forward to the digital era: technology, and the Internet in particular, has drastically evolved and woven itself into the fabric of modern life. By the 21st century, the internet had become the foundation of society – powering businesses, connecting homes, and fueling our daily interactions. In its early days, many viewed the internet with utopian optimism, envisioning a global village of freely shared knowledge and genuine connection. However, as the internet expanded, it underwent a transformation from a “quaint, quirky place” of idealism into an algorithm-driven reality dominated by corporate platforms. What began as an open space to forge “friendships” and engage in communities eventually turned into a homogenized social media environment geared toward maximizing profit. By the time giant companies figured out how to monetize this realm, “we were all hooked on the likes, hearts, retweets, and followers and the boost they gave to our egos,” happily replacing real-life bonds with virtual ones. In short, the social promise of the internet gave way to the demands of advertising and endless engagement. The idealistic “information superhighway” gradually became a crowded, monetized gridlock.

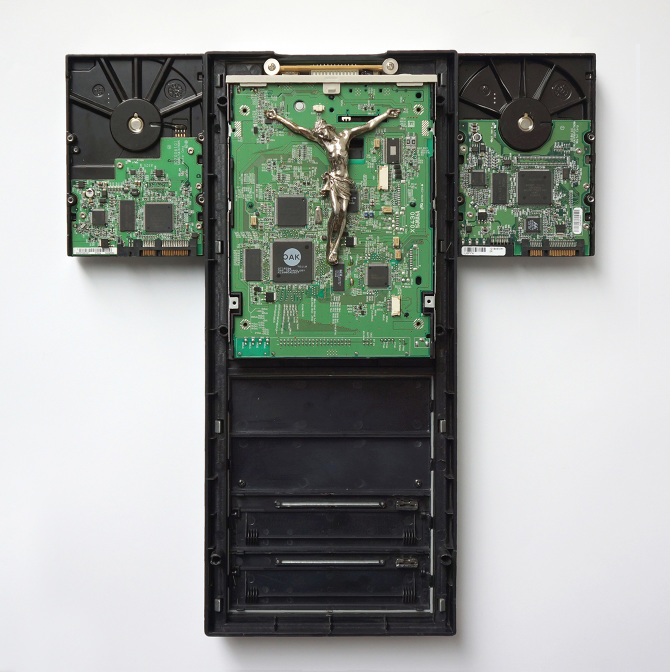

Digital Triptych, assemblage,Stane Jagodic, 1999-07

Digital Triptych, assemblage,Stane Jagodic, 1999-07

Amid this evolution (or devolution), a provocative question arose: Has the Internet died? The “Dead Internet Theory” crystallizes this creeping fear. At its core, Dead Internet Theory is “the belief that the vast majority of internet traffic, posts and users have been replaced by bots and AI-generated content”. What sounds like a conspiracy theory gained traction around 2021 as users observed the web feeling strangely empty and repetitive. Proponents of this theory suggest that the internet effectively “died” around 2016 or early 2017, thereafter becoming “empty and devoid of people” – an online world populated largely by automated content, where one sees “the same threads, the same pics, and the same replies reposted over and over”. Indeed, as artificial intelligence and algorithmic content curation have risen, many have noted that large swaths of online activity seem hollow or automated. Studies and reports increasingly affirm that the internet is now “bots all the way down” – fake but clickable articles produced by AI, bot accounts amplifying “sloppy” low-quality posts, and click-farms turning engagement into ad revenue. In essence, the vibrant, human-driven web that once was appears to be suffocating under an avalanche of algorithmically generated noise. The Dead Internet Theory, while not literal truth, poignantly captures a real sentiment: that the internet’s golden age of organic human exchange has ended, and a kind of death or decay has set in. This notion of the internet’s “death” sets the stage for the artwork’s central metaphor, casting the Internet as a once-living entity now in decline.

Parallels Between Jesus’s Crucifixion and the Collapse of the Internet

The artwork draws a daring parallel between an ancient spiritual tragedy and a contemporary technological collapse. In the Christian narrative, Jesus’s crucifixion is a moment of profound loss — the beloved savior is executed in an act of cruelty and betrayal, even as that very act becomes the means of humanity’s salvation. In the modern narrative suggested by the artwork, the “death” of the Internet is likewise portrayed as a cataclysmic loss — the demise of a creation that once promised to enlighten and connect humanity. On the surface, these two events are worlds apart, yet the artwork invites us to explore their similarities.

Both are stories of sacrifice. Jesus is sacrificed on the cross, offering redemption to others; the open Internet, one might say, has been sacrificed on the altar of commercialization, misinformation, and misuse. Both involve betrayal. In Jesus’s case, he is betrayed by one of his own disciples and condemned by the very people he came to save. In the internet’s case, we might consider how the platform that was meant to serve humanity was “betrayed” by various actors: corporations exploiting user data for profit, malicious agents spreading falsehoods, and even users (like us) trading quality and truth for convenience and instant gratification. In the biblical crucifixion, an innocent being suffers due to the sins and fears of others; in the digital crucifixion, the ideal of a free and open web suffers due to society’s worst impulses online.

Another parallel lies in the notion of a scapegoat. Christian theology interprets Jesus’s death as a sacrifice for the sins of humankind — he bears our faults. In a sense, one could argue the internet has come to bear the ills of modern society: it reflects and amplifies our divisions, our obsessions, our desires for quick answers and entertainment. We sometimes heap blame on “the internet” for social problems (disinformation, polarization, addiction), as if the medium itself were the culprit, when in fact it is our own human behaviors mirrored there. Thus, the crucifixion of the Internet in this artwork can be seen as a mirror held up to our collective conscience. It suggests that the internet — initially hailed as a savior of information — is now being martyred, and we must ask why and by whom.

The crucifixion of Christ, however, is not the end of the story; it is followed by the hope of resurrection. This offers a subtle question in the artwork’s analogy: if the internet as we knew it has “died,” is a resurrection possible? Just as Easter morning brings new life and victory over darkness, could there be a rebirth of an internet that is authentic, human-centric, and free from the forces that brought about its downfall? The piece does not give answers, but the parallel prompts us to consider whether this “death” is permanent or if, through reflection and change, a revival of the internet’s original promise can occur. In drawing these parallels, the artwork fuses ancient and modern narratives, suggesting that the story of a savior’s demise and the story of the internet’s demise are both, in their own way, cautionary tales of hope, betrayal, and the possibility of rebirth.

Digital Illusturation, RUGZOX, 2025

Digital Illusturation, RUGZOX, 2025

The Circuit Board as a Contemporary Sacred Object

In this artwork, the visual centerpiece is striking: the printed circuit board itself has been transformed into the crucified form of Christ. The artist renders the silhouette of the Crucifixion with the aesthetic of a circuit diagram – intricate copper traces and silicon chips replace the hallowed body of Jesus on the cross. In doing so, a piece of modern technology is elevated to the realm of the sacred. The circuit board, normally seen as a mundane component of our devices, here takes on the role of a holy relic or icon. The composition effectively turns the circuitry into a sanctified object, as if the very infrastructure of the Internet were a martyr on the cross.

This creative choice speaks volumes about how we view technology in contemporary life. In our modern era, technology has assumed a role akin to religion for many people. As one futurist quipped, “Technology is the new religion, Silicon Valley is the new chosen land and entrepreneurs are the new chosen people. They promise a future that is better than we think – a techno-heaven of abundance and, naturally, immortality. And we are all believers now”. Indeed, so much of daily life is mediated by digital devices that our dependence on them can feel almost spiritual. We devote immense time and attention to our screens, place faith in algorithms to guide us, and seek comfort in the constant connectivity they provide. By turning a circuit board into a crucifix, the artwork pointedly asks us to consider this quasi-religious devotion to technology. Are we, in effect, worshipping at the altar of the Internet and its gadgets? The glowing screens in our hands have become like prayer candles, and data centers are the new cathedrals where our information “souls” reside. The circuit board crucifix suggests that the Internet’s physical backbone has become a kind of contemporary idol — one that commands reverence but is also an object of sacrifice.

"Digital Constructivism" by Stane Jagodic. Developed between 1983 and 2007.

"Digital Constructivism" by Stane Jagodic. Developed between 1983 and 2007.

There is a profound paradox in depicting the circuit board as a “life-giving” yet “consumed” sacred object. On one hand, the internet’s circuitry truly is life-giving in modern terms: it enables the flow of information, knowledge, and even social energy that powers our world. Just as blood vessels carry life through a body, those electronic circuits carry the lifeblood of our digital existence. They are so essential that society might metaphorically “die” without them. (Imagine the world today without the internet – commerce, communication, and knowledge exchange would grind to a halt.) On the other hand, this infrastructure is consumed relentlessly. We demand ever-faster connectivity, we exploit the internet’s resources around the clock, and we discard hardware as soon as it’s obsolete. In a religious context, a sacred object is cherished and preserved, but in our tech culture, even the most critical components are subject to rapid consumption and replacement. By sanctifying a circuit board on the cross, the artist draws attention to how the Internet’s backbone is both revered and destroyed by us. The circuit board is our savior in daily life, yet we “crucify” it continuously through overuse and obsolescence. This duality highlights the self-destructive cycle of our relationship with technology: the Internet gives us life (information, connection, convenience) even as we figuratively consume that life until the system falters.

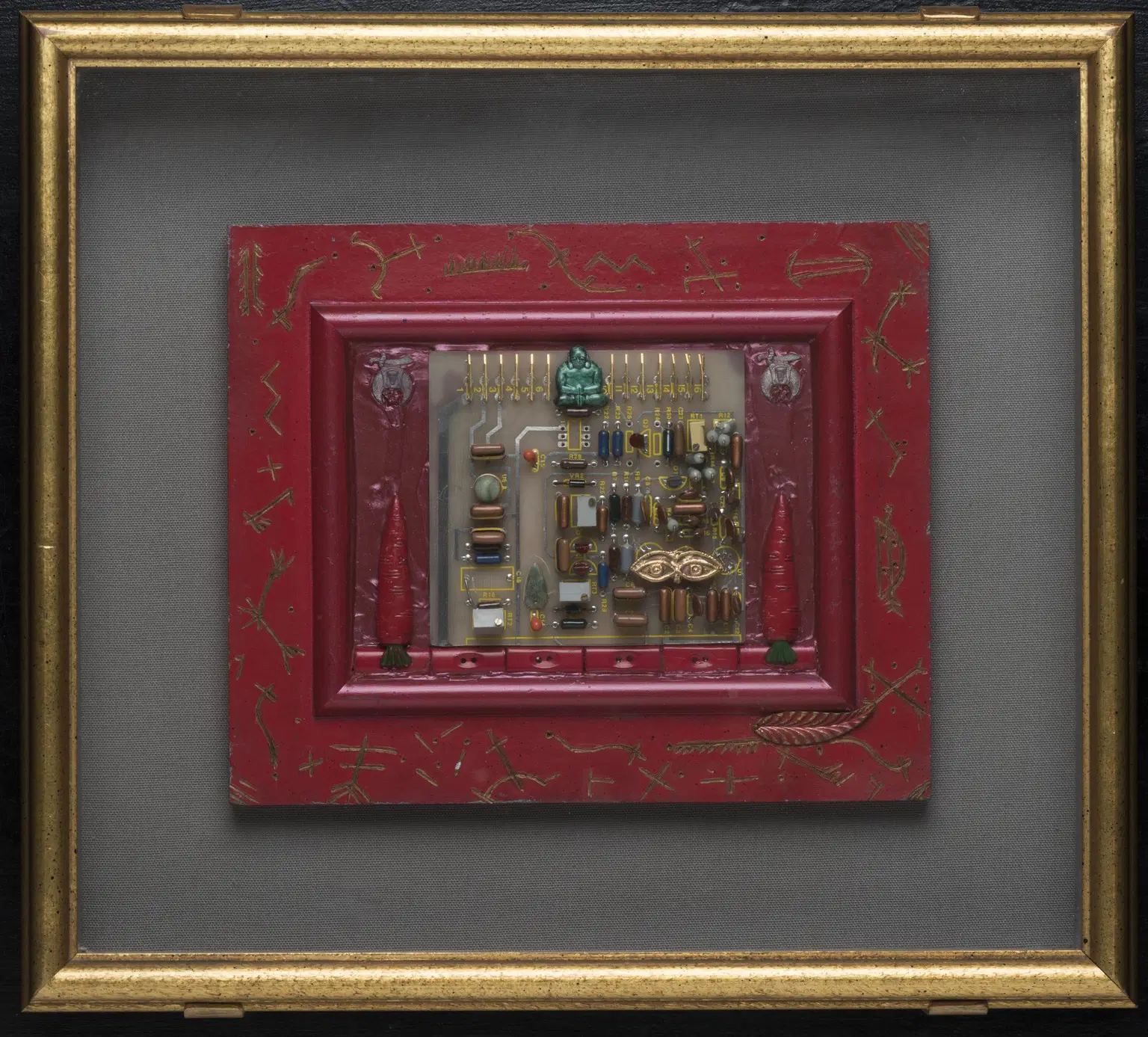

Notably, contemporary artists have explored similar themes by blending technological materials with spiritual symbolism. For example, American artist Betye Saar has incorporated computer circuit boards and chips into her assemblage artworks dealing with mysticism and “sacred symbols,” effectively bridging the gap between the technological and the spiritual. Such works underscore the idea that circuitry can carry symbolic weight, much like religious icons do. In this artwork, the circuit board crucifix becomes a powerful visual metaphor: it is at once an object of veneration and a victim of sacrifice. This invites us to reflect on how the Internet’s infrastructure – the hidden circuits and servers – has become the unseen sacred heart of our civilization, providing vitality while being perpetually exploited. We are left to ponder whether in our fervor for all things digital, we have sanctified technology only to ultimately sacrifice it.

"Betye Saar "Sacred Symbols", 1988. Wood, pigment, framed: 12 1/8 x 13 5/8 in. (30.8 x 34.6 cm), Brooklyn Museum.

"Betye Saar "Sacred Symbols", 1988. Wood, pigment, framed: 12 1/8 x 13 5/8 in. (30.8 x 34.6 cm), Brooklyn Museum.

Similarities Between the Corruption of Belief Systems and the Degradation of Information Systems

Beyond the immediate religious and technological imagery, the artwork also prompts contemplation of how belief systems and information systems can deteriorate in analogous ways. In history, when religious institutions became corrupt – when clergy sought power and wealth, or when dogma stifled truth – the faithful experienced crises of belief. One might recall how the excesses and corruption in the medieval Church led to the Reformation; people’s trust in the prevailing religious system was so broken that it spurred a revolution of faith. In modern times, Nietzsche’s famous declaration “God is dead… and we have killed him” was not merely about theology, but about the collapse of a whole structure of meaning and truth. It signaled that the old certainties had disintegrated, leaving a moral and spiritual void. Similarly, consider what has been happening with our global information ecosystem. The internet – our great modern tool for truth-seeking – has become rife with misinformation, manipulation, and mistrust. Many observers now speak of a “post-truth” era, where objective facts have lost their power to persuade. In other words, the authority of truth itself is under siege, much as the authority of the Church was once under siege.

The parallel is striking: just as the abuse of religious authority led to widespread loss of faith, the abuse of information channels has led to a loss of faith in what we read and watch. People today often do not know what or whom to believe. Every day, we witness how easily truth can be subverted online. Algorithms favor engagement over accuracy; trolls and propagandists sow doubt and division; social media feeds become echo chambers of half-truths. As experts have warned, our online activities can “undermine truth” and “foment distrust,” weakening the very foundations of an informed society. The integrity of our information systems has been compromised, just as the integrity of certain religious institutions was compromised in the past. In both cases, the fallout is a kind of cynicism and disillusionment. The faithful ask, “Whom can we trust? What is sacred?” – be it in a church or on a newsfeed.

In the artwork’s context, the corrupted code of the internet and the corrupted creed of a religion intersect on the symbolic crucifix. It suggests that whether it’s a Bible or an algorithm, a priesthood or a platform, the potential for decay and misuse is always present – and the consequences can be dire. Belief systems (spiritual or secular) rely on trust and authenticity. When that is eroded, people feel unmoored, betrayed, even existentially shaken. We might draw a comparison between, say, the scandal of indulgences (where the promise of salvation was sold for profit in the 16th century) and the scandal of user data exploitation or fake news (where the promise of a free flow of information was distorted for profit or power in the 21st century). In both scenarios, an ideal was tarnished by human greed and deception.

AI Generated "Dead Internet Image" RUGOX, 2025

AI Generated "Dead Internet Image" RUGOX, 2025

The crucifixion of the circuit board can thus be seen as the collapse of a belief: the belief that technology would always be a force for good, or that the internet would naturally disseminate truth. Like a religion marred by hypocrisy, the internet’s reputation has been marred by its own vices. The symbiotic relationship between faith and truth – once intertwined in religion, now in our relationship with information – is broken in both cases. This artwork merges the two realms, urging the viewer to consider the collective loss of innocence. The death of Christ in Christian belief was also a death of the disciples’ naïveté, forcing them to reconcile their expectations with a harsh reality. The “death” of the internet’s ideal might likewise force us to confront the reality that the systems we trusted to sustain truth and community have been perverted. The question then becomes: What do we do in the wake of this loss? In Nietzsche’s words about God’s death: “What festivals of atonement, what sacred games shall we have to invent?” In other words, how do we fill the void and seek redemption when both our spiritual and informational foundations falter? The artwork leaves us with this open-ended challenge, encapsulated in the merged image of the cross and the circuit: a stark reminder that when belief and truth alike are crucified, the soul of society hangs in the balance.

Questions to Ponder: Who Killed the Internet? Did We Crucify It?

Standing before this artwork, the viewer is inevitably confronted with a moment of introspection. The jarring fusion of the cross and circuitry compels us to ask uncomfortable questions about responsibility and complicity. In the biblical narrative, one might ask who was responsible for Christ’s death – was it Judas who betrayed him, the authorities who sentenced him, or the crowd that demanded Barabbas be freed instead? The answer is complex, often coming back to the theological notion that humanity’s sins collectively necessitated the sacrifice. In the case of the internet’s “death,” the artwork pointedly turns the question toward us: Who killed the Internet? Is there a single culprit, or have we all played a role in crucifying it? Every click on sensationalist fake news, every time we valued convenience over privacy, every instance we allowed rage or fear to go viral unchecked – are these the nails in the digital cross? The piece suggests that the internet’s demise is not an abstract event but a human-made tragedy in which we are participants, not just observers. As one commentator noted in hindsight, we eagerly allowed social media to lure us in, became “hooked on the likes” and trivialities, and were “happy to replace real-life friendships with an unlimited number of online friends”, thus handing over the soul of the internet to forces of manipulation. In doing so, did we pave the way for its downfall?

RUGZOX, Dead Internet (2025), Digital collage

RUGZOX, Dead Internet (2025), Digital collage

The artwork leaves these questions hanging in the air, unanswered. It does not preach or resolve, but rather, like a mirror, it reflects our own actions back at us. In the end, we must consider: if the Internet is “dead,” did we as a society have a hand in killing it? And if we acknowledge our part, is there hope for atonement or resurrection? The crucifixion imagery inherently asks us to contemplate guilt, forgiveness, and redemption. Transposed onto the digital realm, it urges a kind of digital soul-searching. The viewer is left to wonder whether the “death” of the Internet was inevitable or a consequence of our choices – and whether we have the will to revive what has been lost. These provocative questions linger as one steps away from the piece, much like the silence after a profound ritual or revelation:

Who killed the Internet? Did we crucify it?

References

- "Dead Internet Theory," Wikipedia

- "The 'dead internet theory' makes eerie claims about an AI-run web. The truth is more sinister," UNSW Newsroom

- "The Deeper Symbology of the Cross," Medium

- "What the Crucifixion of Jesus Symbolizes," Unity.org

- "The Dead Internet Theory, Explained," Forbes

- "The Dead Internet Theory: A Survey on Artificial Interactions and the Future of Social Media," arXiv

- "The symbolism of the cross," Billy Graham Evangelistic Association